The Power of Words

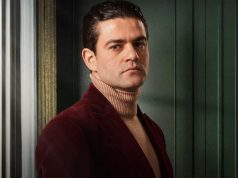

Celebrated Egyptian- American Poet Yahia Lababidi By Hilary Diack

Poet, aphorist, savant, and author of works that have been translated into more than nine languages, Yahia Lababidi recently opened up to Cairo East Magazine about his new book Balancing Acts: New & Selected Poems (1993-2015) and his journey thus far. The author of three poetry collections, Balancing Acts: New & Selected Poems (1993–2015), Barely There and Fever Dreams; an essay collection, Trial by Ink: From Nietzsche to Belly Dancing; and a collection of aphorisms, Signposts to Elsewhere, selected as a 2008 Book of the Year by The Independent (U.K.), amongst many others, his works evoke the spirit of poets that remain today part of the cultural heritage of many nations. Literary credentials apart, the man himself is eminently approachable and exudes the gracious responsiveness that is afforded those who are present in the moment, a cornerstone of his philosophy.

CEM: How was poetry first introduced into your life?

YL: I believe that the artistic life is a calling, and a life of service. More concretely, there are many factors that conspired to make this possible. Part of it is nature: I was named after my paternal grandfather, Yahia Lababidi, who was a celebrated poet and musician. (And, even though he passed away long before I was born, I believe he passed more onto me than his name). Part of it is nurture; I was raised in a fairly creative environment where my parents hosted an informal literary salon and, at a very young age, was surrounded by poets, artists and thinkers.

How did you become fascinated with the great classical poets?

Since I was a restless teenager, looking to escape my complicated self and circumstances, I read to get drunk and, to paraphrase the French poet, Baudelaire, hoped to stay that way. A handful of slim volumes altered my intellectual/spiritual landscape and, at the risk of melodrama, saved my life! Past the intoxicating, aesthetic experience, these books knew me before I did and confessed my secrets—speaking the yearnings of my still-inchoate soul far more eloquently than I could ever dream

at that bewildered age. Sensing my desperation and need, I believe that Literature reached out, presenting me with a world more real and alive than any other I inhabited.

Who in your life has been the greatest inspiration?

There is no one person, different authors at represented different stages, seemed to arrive like a hand in the dark. As a Lebanese-Egyptian, Gibran was an early and inescapable influence. Then there were various poets, novelists and philosophers that I felt called out to me as a young man, such as Hesse, Dostoevsky, Kafka, Eliot, Wilde, Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Rilke, Rumi. Increasingly, I draw sustenance and inspiration from Sufi saints and mystics. You can find readings of poetry that matters to me, here, on my SoundCloud page: m.soundcloud.com/yahia-lababidi

Your published works have always been well received, what do you feel resonates so strongly with your readers?

Kind of you to say. Reader response is always a mystery and a blessing. Much as I am grateful for it, I’m hardly aware of an audience when I’m writing. I think of writing as an act of confession and praise, speaking to the blank page as if it were the last person on earth. Something of this emotional vulnerability, akin to nakedness, is what readers appreciate (perhaps, even expect of their literary artists). Though one might deceive themselves into believing otherwise, Poetry is never a personal enterprise; a poet sings for those who cannot.

What is the emotional impact of compiling so many years of musings, poetry and experiences into this new volume?

Seeing 1993-2015 on my book cover is a little like contemplating my own tombstone. Here lies a life, in Poetry. It is humbling and bewildering to meditate over 2 decades of one’s being and becoming, in verse. As Yevgeny Yevtushenko puts it: “A poet’s autobiography is his poetry. Anything else is just a footnote.” But, with this metaphorical tombstone, and the closing of a book on several chapters of one’s life, comes the liberating and enticing possibility of rebirth.

You capture and record your thoughts so well, are there any that escape, and do you hunt them down?

The poet tries hard, yet, much of the poetry slips the poem’s net. All languages are rough translations of our native tongue: the Spirit. Perhaps the best of poetry is lost in translation, since the essence of our experience is irreducible. This is why artists are scarcely ever fully satisfied with their art. “Between the idea/And the reality/Between the motion/And the act/ Falls the Shadow”

– T.S. Eliot >>

Below, is a poem of mine, from my new collection, where I attempt to say this unsayable truth:

Ars Poetica

Words in a poem are merely the tip of the iceberg, the bulk of poetry belongs to a mass beneath the surface.

Invisible words trail the visible and give them force just like printed paper, backed by gold, gains in value.

But, what can we do, we work with what we have using the modest symbols we possess to speak of that which we do not own. Like incantations, certain combinations set a sentence or soul in motion.

It’s the same with artists who use shadow to bring out light or musicians who lend instruments their breath and limbs, to summon music from thick air. So, too, with poets who conjure hidden correspondences with letters.

Which is to say, words only matter up to a certain point (when you’re using words to lose them). A poem is only as good as the unseen poem it mirrors or, to tell it straight, the Spirit that it harnesses and which swims through it.

How important are prose and poetry in breaking down cultural barriers and misconceptions?

Well, despite its limitations, all we have is language to communicate with one another and we must try to make do with these imprecise tools and symbols. Living in the US at this historical moment, for example, when there is mounting suspicion and murderous ignorance in regards to the “Arab/Muslim world”, I do feel a kind of responsibility for my writing to serve as a kind of bridge, or peace offering, addressing our shared humanity. Prose can do that, by tackling misconceptions directly, poetry does it by attempting to tell the truth slant. One way I’ve found, lately, is to try and communicate through my short meditations, or aphorisms, what I’ve found inspiring in Sufism (the mystical branch of a little understood and much-maligned faith: Islam).

“Ah, to be one of them! One of the poets whose song helps close the wound rather than open it!” —Juan Ramón Jiménez

Do you visit Egypt often, and how do you feel about it?

Yes, I visit Egypt often in my dreams, and vicariously through friends and family, even though I’ve not been back in person for an incredible 10 years, now! In fact, my new book is dedicated to “Egypt, the real and imaginary Home I carry in my heart.” Kindly, find here two poems from Balancing Acts that speak me better than myself on this overwhelming and emotional subject:

Cairo

I buried your face, someplace

by the side of the new road

so I would not trip over it

every morning or on evening strolls

still, I am helplessly drawn

to the scene of this crime

for fear of forgetting

the sum of your splendor

then, there’s also the rain

that loosens the soil

to reveal a bewitching feature

awash with emotion

an eye, perhaps tender or

a pale, becalmed cheek

a mouth, tight with reproach or

lips pursed in a deathless smile

other times you are inscrutable

worse, is when I seem to lose you

and pick at the earth like a scab

frantic, and faithful, like a dog.

Egypt

You are the deep fissure in my sleep,

that hard reality underneath

a stack of soft-cushioning illusions.

Self-exiled, even after all these years

I remain your ever-adoring captive.

I register as inner tremors

– across oceans and continents –

the flap of your giant wing, struggling

to be free and know I shall not rest until your glorious metamorphosis is complete.

Aphorisms:

A good listener is one who helps us overhear ourselves.

The thoughts we choose to act upon define us to others, the ones we do not define us to ourselves.

Temptation: seeds we are forbidden to water, that are showered with rain.

Impulses we attempt to strangle only develop stronger muscles.

Ambiguity: the bastard child of creativity and cowardice.

Truth can be like a large, bothersome fly – brush it away and it returns buzzing.

In life, as in love, graceful leave-taking is the epitome of gratitude.

To be treated with mercy, some must reveal their handicaps, while others must conceal them.

To hurry pain is to leave a classroom still in session.

Like cars in an amusement park, our direction is often determined through collisions.

The personal made universal is art’s truth.

Romantic: one who professes to prefer the thorns to the rose.

– Signposts to Elsewhere