The Penguin of Many Forms

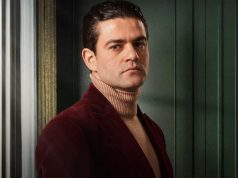

Actor, Producer, Poetry-Lover, Legend

By Shorouk Abbas & Francesca Sullivan

Behind a formidable desk in the office of his production company in Heliopolis, Mahmoud Hemeida sits reading a book of poetry while listening to Tchaikovsky. Charisma radiates from him like a heat-seeking missile, yet he appears calm and poised with an eyebrow that lifts sardonically at the slightest provocation. Above the desk a large plaque declares the name of his company to be ‘The Penguin’. Can he explain? He waves a graceful hand towards it and obliges, “There is a line of poetry by Fouad Haddad that I have always loved. It says we are birds with wings and sandals; we should be free like birds, but still grounded. The penguin is the king of birds, yet doesn’t fly.”

Poetry is a big part of his life and he reads it daily. Like the penguin on his wall, Hemeida is nothing if not grounded, and with his own singular way of approaching life. “I live for the moment, I enjoy myself, but I question everything,” he declares with pride. “When I was a baby I walked and talked early; I didn’t like it when adults talked down to me.”

A precocious child then? “Yes,” he smiles, “I like that word. When as a kid I discovered that it’s normal to sleep eight hours an night I was appalled – I didn’t want to spend one third of my life sleeping! I trained myself to have two hours only, and get up at dawn.”

Born in 1953, Hemeida has been acting on and off since the age of five (he took lead roles in school productions), but by his own admission has also done every job under the sun in between. Brought up between the urban family of his mother and the rural roots of his father, he learned to be equally at home in both environments. Then, when he got to university, he became something of a rebel, and ended up working as a labourer on a building construction site and as a dancer, taking classes in ballet, swing, rock and roll and folklore styles, performing gigs as part of a troupe. He eventually graduated as an accountant, worked as a salesman for a soft drinks company, got married, and seemed set for a conventional life, with part-time acting on the side. But in 1990 – a time when ironically the local movie industry was struggling – he finally gave himself up to a full time acting career.

“I’d done quite a lot of stage work, but I only truly entered the film world in the 1990’s. I found I preferred film to theatre. I really enjoy the process of building a character slowly, brick by brick.”

Such a varied life has given Hemeida a decidedly worldly aura. In a crowded room he stands out, not only because he is tall, but because of his extraordinary presence, and a dazzling charm that he can switch on and off at will. He has the assured, twinkling air of a gentleman who might also be a rogue – and lately he has played not just one but two undoubted rogues in two separate movies, each on opposite sides of the law: Minister of the Interior in Ott we Far, and an underworld career criminal in Regatta.

The latter hit controversy before its release by falling foul of the censors for bad language, though Hemeida brushes this aside. “There was a sentence or two in the trailer that some people found obscene. It was not obscene; it was street language commonly in use. I believe they removed one word.”

More importantly, the role of Ragab in Regatta was one he obviously relished, “The challenge for me was to make Ragab unique, and appealing. When I am playing an evil character I look inside myself to bring that evil out and enable the audience to identify with it, because we all have it in there somewhere. The process is actually a cleansing one; by acting it out I can then release it.”

In the past, identification with the character has been a hazard of the job though. “I’ve enjoyed every role I’ve played, but some have been very heavy. In 2004, after playing a severely crushed personality in Baheb El Cinema I ended up in hospital for six weeks. I felt literally weighed down by mountains of worries.”

This kind of experience prompted Hemeida to analyse and develop his own acting method, which he describes as, “a mixture of techniques that I arrived at by accident. When I first took acting lessons I was seventeen. It was by the book – except that there is no such thing as the book. That’s for the teacher, not the student. Supposedly the teacher is a mirror for the student – only in acting there are no mirrors. In dancing yes, but not acting! So I arrived at my own method by which I became both student and teacher, learning how to be both in the character and outside simultaneously – almost like playing with a marionette.”

Part of this process came through studying bodywork in Alexander and Feldenkrais techniques. “The body is the instrument the actor uses, and we must know our instrument. Everything from blood pressure to nerves to muscles are affected while you are acting, and to this end I studied anatomy to understand and learn to control these things better – and not to end up in the hospital with high blood pressure!”

Poetry and meditation also play a daily role in Hemeida’s life, probably helping to keep that high blood pressure at bay.

“I do half an hour’s meditation daily. When I first began to meditate I didn’t even know that was what I was doing. I would find myself concentrating on something, like a tiny leaf, or I’d lie on the floor and close my eyes.”

Does he write any poetry himself? “No, only what I make up to read to my grand-daughters – nothing serious,” he says. But he is, and has always been, an avid bookworm.

“There is no-one in the world that I’d like to meet that I haven’t already met through books. I remember once I was playing snooker with a friend and I was reading a book about Taha Hussein between shots. When he asked me why, I explained that later that evening I was due to sit with Taha Hussein – meaning in a book – so I was trying to familiarize myself with him. My friend thought I was crazy.”

Yet when it comes to researching a role, Hemeida puts books away. “I always use the script as my reference, nothing else. My aim is to catch the spirit of what the script-writer has created. Even when playing a historical character I refer only to the scenario in front of me.”

Ott we Far allows Hemeida to explore more of a comedy role, something he says he hasn’t had that many chances to do. But he has no preference between comedy and drama. “I like both, and in both I apply myself to the job and get on with it. First and foremost I have to enjoy myself – otherwise the audience won’t be entertained.”

Ott we Far allows Hemeida to explore more of a comedy role, something he says he hasn’t had that many chances to do. But he has no preference between comedy and drama. “I like both, and in both I apply myself to the job and get on with it. First and foremost I have to enjoy myself – otherwise the audience won’t be entertained.”

The eyebrow lifts again, and with such a heavy dose of charm emanating from behind the desk it seems appropriate to ask, what does he find most attractive in a woman?

“Her soul,” is his instant reply. “I see it and I feel it. But sometimes it might be something other people don’t see at all.”

Villain, lover or both, it seems Mahmoud Hemeida has it all under control. In whatever movie you catch him this year, be prepared to be entertained!